Traditional Chinese Theater Culture: An Introduction in English

Chinese traditional theater, epitomized by Beijing Opera (Peking Opera), is a vibrant tapestry of art, history, and philosophy. Below is a structured introduction to its key aspects, suitable for an English essay or cultural overview.

1. Origins and Historical Background

Beijing Opera, known as Jingju (京剧), emerged during the late 18th century. In 1790, during Emperor Qianlong’s reign, four Anhui opera troupes traveled to Beijing to celebrate his 80th birthday. Over time, they blended with local styles like Kunqu and Hanju, forming the foundation of Beijing Opera. By the mid-19th century, it evolved into a distinct art form, combining music, dance, acrobatics, and storytelling.

2. Artistic Features

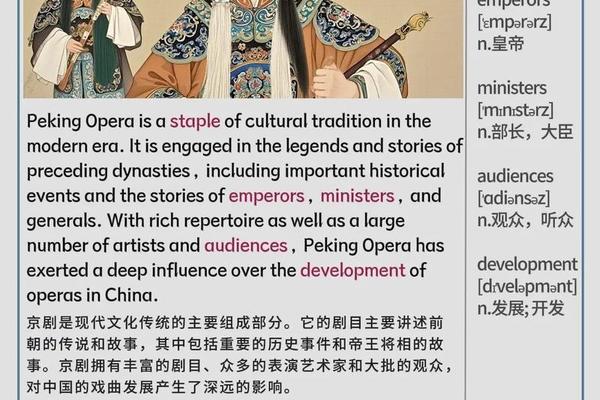

Beijing Opera synthesizes stylized singing (chang), recitation (nian), acting (zuo), and acrobatic combat (da). Performers use exaggerated gestures and symbolic movements to convey emotions like joy, anger, and sorrow.

Costumes are elaborate, hand-sewn with traditional motifs, reflecting historical dynasties (e.g., Ming and Qing). Facial makeup (Lianpu) uses vivid colors to symbolize character traits: red for loyalty, black for integrity, white for treachery.

Instruments like the jinghu (two-stringed fiddle) and drums create a rhythmic backdrop. Vocal styles vary between lyrical melodies and sharp, percussive tones.

3. Role Categories

Beijing Opera characters are divided into four main roles:

1. Sheng (生): Male roles, including warriors and scholars.

2. Dan (旦): Female roles, often graceful or heroic.

3. Jing (净): Painted-face male roles, representing gods or generals.

4. Chou (丑): Clowns or comedic roles, recognizable by a white patch on their noses.

Each role requires rigorous training from childhood, emphasizing agility, vocal control, and emotional expression.

4. Cultural Significance

Plays draw from historical legends, folklore, and classics like Romance of the Three Kingdoms, showcasing virtues like loyalty and justice.

Confucian ideals of harmony and morality are woven into narratives, while Taoist and Buddhist influences appear in symbolic gestures and staging.

In 2010, Beijing Opera was inscribed in UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, highlighting its global cultural value.

5. Modern Challenges and Revival

While traditional audiences are aging, efforts to modernize Beijing Opera include fusion with contemporary theater, digital broadcasts, and educational programs. Artists like Mei Lanfang (1894–1961), who popularized the art globally, remain cultural icons.

Sample Essay Structure (English):

Title: The Splendor of Beijing Opera: A Treasure of Chinese Culture

Introduction: Briefly introduce Beijing Opera as a fusion of art forms with deep historical roots.

Body Paragraphs:

1. History: Mention its origins in the Qing Dynasty and multicultural influences.

2. Artistic Techniques: Describe singing, acting, and symbolic makeup.

3. Cultural Legacy: Link stories to Chinese values and UNESCO recognition.

4. Modern Relevance: Discuss preservation efforts and global appeal.

Conclusion: Emphasize its role in connecting past and present, urging cultural appreciation.

References:

For deeper exploration, refer to historical texts like The Drunken Concubine or documentaries on UNESCO’s website. To practice writing, analyze classic plays or compare Beijing Opera with Japanese Kabuki.

This framework integrates historical depth, artistic details, and cultural context, offering a comprehensive yet engaging introduction to traditional Chinese theater.